by Shenlan Guan / Feb 21, 2021

Published in International Examiner

WeChat Ban Brings Frustration and Anxiety to the Chinese Community

Mobile phones and applications are essential for people’s life. WeChat as a multi-purpose communication application has over 1.2 monthly active users across the world. (Robin Worrall)

When Suyun Zheng, the mother of an international student studying in Boston, recently discussed the Trump Administration’s prohibition of using a popular Chinese messaging app, her voice was breaking.

“I felt panic. I didn’t know what to do anymore,” Zheng shook her head, “Why would this happen? This is our communication channel.”

The channel that Zheng was worried about was WeChat, a Chinese messaging mobile application. Following President Donald Trump’s executive order last August, the Department of Commerce declared a prohibition on transactions using the Chinese mobile applications WeChat and TikTok on September 18, 2020.

Technical professionals analyzed that the order could require internet providers to block technical services from Chinese companies, making WeChat users unable to update the application, experience lagging, lack of function, or impossible to send messages.

There are over 1.2 billion monthly active users of WeChat worldwide. According to analytics firms Apptopia, 19 million of its active users are located in America.

The prohibition worried Zheng’s family. Suyun Zheng is a junior high school teacher in Guangzhou, China, and a mother of a 24-year-old international student. Her only child has relocated to Boston in August 2019 and recently graduated from Boston University with a master’s degree.

WeChat is the primary communication method between Zheng and her son. Since the son moved to Boston, Zheng chats with her son on WeChat three to four times per week to talk about food, work, and social news.

When Zheng heard about the prohibition of WeChat, the first backup application that she could think of was Tencent QQ, an instant messaging software developed by the same company as WeChat. She notified her son immediately and tried to communicate there.

“My family, my best friends, and my students are all on there,” said Zheng, “I won’t use anything other than WeChat unless I’m running out of choice.”

Kathy He is posing on Zhangjiajie Yuntiandu Glass Bridge in Hunan, China, September 2019. He is a Chinese American with family members located in two countries, WeChat becomes an important messaging application for her personal life and career. (Photo provided by Kathy He)

Zheng is not the only one who is desperately finding a backup messaging application.

Kathy He, 21, is a senior interdisciplinary visual art student at the University of Washington. She fears the financial pressure if the application ban is activated. He was born in Saipan, CNMI, and came to Seattle with her friend in 2017 after graduating from high school.

Before the pandemic, she worked for about 20 to 30 hours per week to support her education and daily expenses. The messenger application WeChat becomes vital support for her income.

“I have about 150 people in my contact list, and about 40 of them are my ‘baba,’” She said. “Baba” in Chinese means father, He was using the Mandarin slang for “dad” to describe her loyal clients.

In Chinese internet culture, “client baba” stands for long-term, stable business partnership. As a part-time sales supervisor of a luxury brand, He has close contact with a list of bulk buyers. Without these bulk buyers, He could lose up to 20% of her business during the sale seasons. He emphasized that WeChat is connecting her with these “pillars of life.”

If the application ban takes place, she could find backup communication methods with her family and friends. Still, it would be challenging for her to rebuild her business network.

“I was mad, very mad,” He recalled her first impression when she heard about the application ban, “Every ‘client baba’ is very important to me. I can’t afford to lose them.”

As an art student, He uses Tencent QQ to exchange experiences with other artists from different communities. When the Trump administration announced the application ban in August 2020, she considered Tencent QQ as an alternative platform to keep in touch with friends and family.

He’s family members make her believe that WeChat is the best messaging option for her situation. Her grandparents, who live in China, took a long time to get used to WeChat. He does not want the elderly to get confused by another technology product.

But Jingran Meng, an international student at UW from Beijing, listed many more backup applications when she learned about the ban. “Not just [Tencent] QQ, all of my friends were exchanging LINE and WhatsApp as well.”

Meng looked back on the executive order, “[The ban will] affect my quality of life very negatively.”

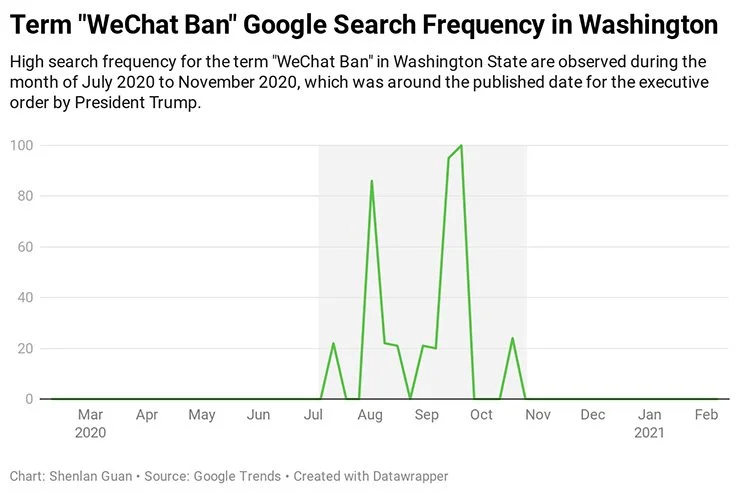

There are a large number of people who share Meng’s anxiousness. According to Google Trends data, the Google search frequency for the term “WeChat Ban” in the United States peaked from zero to an all-time high from July 2020 to September 2020. In comparison to other states, Washington state ranked No.6.

Meng came to America at the age of 18 to study mechanical engineering at University of Washington. With no friends or relatives when she arrived here in America, Jingran Meng and her family chatting on WeChat daily.

Today, Meng has been taking classes online back home in China because of the pandemic. Meng’s three best friends live in UW student dorm in Seattle, and WeChat is their fundamental communication platform, which lets Meng take the application ban very seriously.

The unpredictable updates of the WeChat ban brought generated complicated emotions for many WeChat users. After a US Magistrate Judge blocked the ban application, the Trump administration published another executive order on January 8, which includes the prohibition of all transactions from WeChat and the backup plan for many WeChat users — Tencent QQ.

Yet, on February 11, on the Lunar New Year’s eve, the Biden administration paused this second round of the Chinese application ban. Since the publication of the second ban, Suyun Zheng was constantly in fear of losing connection with her child. The pause was a huge relief for her.

“I am so happy that I can stop worrying now.” said Zheng, “My child and other international students are so far away from home for a long period. Worried and sadness have become the regular emotions for [the students’] parents.”

Jingran Meng also found comfort from the pause of the ban, and she is no longer worrying about WeChat’s usage in America. Meng placed her faith in the new president, as she hoped the new administration might ease some tension between the US and China.

Kathy He, on the other hand, suggested the future of WeChat remains unclear.

“I hope WeChat will not be the victim of the political battle between U.S. and China,” He said softly. “In the end, Chinese communities and Chinese Americans are going to be the ones who suffer.”