Public Opinion Among Images:

A Thematic Analysis of 2019-2020 Hong Kong Protest Online Images via Hashtags and Search Terms on Facebook and Weibo

Abstract

I conducted thematic analysis research of the online images about the 2019-2020 Hong Kong Protest on two platforms that are considered very popular across different regions: Facebook and Weibo.

The Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement (反送中运动), also known as the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests, is a series of demonstrations responding to the Fugitive Offenders Amendment Bill by the Hong Kong government. This anti-bill movement is one of the largest series of demonstrations in the history of Hong Kong since 2014, the Umbrella Movement. The protest started on March 15, 2019, with a sit-in at the Hong Kong government, and the movement has been taking a pause since the new law National Security Law was passed by the Beijing government (国安法). The Beijing government declared that peace and stability had been restored to Hong Kong ever since June 30, 2020.

There are a large number of images produced for the movement, differing from “pro-HK” to “pro-China,” presenting many political or economical “sides” along with different regions and different language users on the social media. The conversation using videos, images, memes, and other forms of visual media peaked on many platforms during the protest.

I wish to discover the impact of the polarization of public opinion in cyberspace during the protest event on the nationalism of citizens of Hong Kong. One of the many struggles that the people of Hong Kong are fighting through, is making meaning out of their political and national identity, their ethnicity, and political rights on the land between China and the rest of the world. The international attention that the Hong Kong protest gained has echoed on social media and changed the direction, progress, and the future of the event.

This thematic analysis is the beginning of the discovery, exploring some patterns of visual communication between different media platforms. This paper will focus on thematic analysis over still visual media. I will perform the analysis on the following platforms: Facebook, the world’s leading and most popular social media platform. And Weibo is the most popular social media platform in mainland China.

Research Introduction

The purpose of this study is to collect and analyze visual data in order to answer the following research questions:

What are the themes of still visual media posts during the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests across Facebook and Weibo?

Is there a relationship between themes versus hashtags/search terms, platforms, and regions?

Are the themes of visual media posts of the protest indicating public opinion polarization?

I collected data through hashtags and search terms access. By filtering out the posted date and media type, I collected a minimum of 30 and a maximum of 100 images under each hashtag or search word entry. After organizing the data, I followed the six steps of deductive thematic development by Braun and Clarke: familiarizing, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, then discussing the result.

I have collected a total of 608 photos from the two platforms accessing through five hashtags or search terms per platform. There are a total of 273 photos collected from Facebook, and the hashtags are “#香港游行 (Hong Kong protest),” “#freehongkong,” “#反送中 (anti-extradition to China),” “#和理非 (peace, reason, non-violence),” and “#chiNazi.” There are a total of 335 photos collected from Weibo, and the search terms are: “香港游行 (Hong Kong protest),” “香港加油 (Hong Kong add oil),” “反送中 (anti-extradition to China),” “和理非 (peace, reason, non-violence),” “废青 (garbage youth).”

The analytical plan is to identify the type of the images, provide a description of distinguishable elements in each image, pin down any strong political symbol, rate the information of each image by extremity, generate common patterns then review and name the themes.

There are 12 themes identified from the protest images, no significant relationship was found between themes versus hashtags/search terms, platforms, and regions, but there are indications of public opinion polarization.

Data Collection

There are three universal rules for all hashtags and search terms image collection under every platform, then I executed with exemption and practiced within limitations. First of all, the media that I collect must be still visual media. Video is one of the most popular visual media spread during the protest, but it has very different communication effects with respect to photos. In order to perform the analysis uniformly, I excluded all the motion media, which indicates I excluded an essential communication channel and a significant amount of data. Secondly, all images must be posted from March 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020. The first recognizable event of the protest was the March 15, 2019 sit-in, organized by Demosistō at the Central Government Complex of Hong Kong. I included the date till the first of March for the possibility of early discussion or event organization. The discussion of the Hong Kong protest is still very popular today, and I end the posted date at the end of July 2020, about one month after the National Security Law was activated. The last rule is I must include all results that fall under rules one and rule two. If the media is still visual media, it was posted with the selected hashtags or search terms, and it is posted between the selected date, then I will include the image regardless of the content, despite whether I believe that image is related to the protest or not.

I selected five hashtags and search terms per platform. I attempted to select hashtags and search terms with similar literal meanings or communication patterns on the two platforms. For instance, I put in “香港游行 (Hong Kong protest),” “#反送中 (anti-extradition to China),” and “和理非 (peace, reason, non-violence)” as the same search entries on both platforms. Then I choose one hashtag that is very popular on Facebook, “#freehongkong,” and “香港加油 (Hong Kong add oil)” for Weibo. Lastly, I choose two phrases with strong emotion, as well as two popular hashtags and search terms, they are “#chiNazi” and “废青 (garbage youth),” an internet slang among Mainland China describing the young protestors of Hong Kong. When I was collecting images from Facebook, I included up to the first 100 results. When I was collecting through Weibo, I applied the advanced search filter, entered the result date posted from March 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020, selected the ranking of popularity, and included up to the first 100 results.

Search Entry

Facebook

#香港游行 - same entry

#freehongkong - similar popularity

#反送中 - same entry

#和理非 - same entry

#chiNazi - strong emotion

Search Entry

Weibo

香港游行 - same entry

香港加油 - similar popularity

反送中 - same entry

和理非 - same entry

废青 - strong emotion

However, there are some limitations and interesting findings during the collection process. On Facebook, there is a significant difference between hashtags and search terms, and the advanced search function is difficult to apply. If searching by search term, Facebook can only present very few search results. When searched by hashtag, the search results under each hashtag are ranked unexpectedly. It is not ranked by popularity or posted date. And there is no pattern found during the collection to name the ranking order. On a few occasions, the end of search results is very surprising. For example, under the hashtag “#反送中 (anti-extradition to China),” the landing page indicated that there are 4.3K people posting about this hashtag, but I could only collect 66 images.

The Weibo collection, on the other hand, must go through search terms. Because of the political nature and the platform community guideline, there are very limited hashtags available. For example, if I enter “#香港游行# (Hong Kong protest)” as a hashtag entry, it came back with zero results. But if I enter the same keyword as the search term, the results are endless. This indicated that the users of Weibo discussed the Hong Kong protest with high passion, and the images posted are worth analyzing. Because of the different approaches to accessing images, there are cases where the same photo showed up repeatedly. That could be due to multiple users reviewing a related article from the third platform, and sharing it on Weibo that included the same context and same image. Even though the advanced search function supports ranking the result by popularity, this type of situation indicates one image related to an article could be very popular, but the number was disputed across different users. Moreover, the popularity ranking is promoting users with a larger number of followers and interactions. This indicates, that some images with a high number of reactions, comments, and share rate, could be due to the higher traffic to the same account, but not the content of the image itself. This situation must be considered while discussing what themes of imagery travel faster.

As popular as this topic is, it is important to recognize the censorship of the posts. Many protest-related posts are taken down from Weibo due to two main reasons: the content of the post is challenging the Beijing center authority, or the post is questioning or disagreeing with the “one country, two system” policy. This situation also led to self-censoring. In order to protect the posts from being taken down, the platform users are either not posting about related topics, or created new terms and slang to discuss the issue. For example, “颜色革命 (color revolution)” is a new slang created for the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protest

Analysis Application

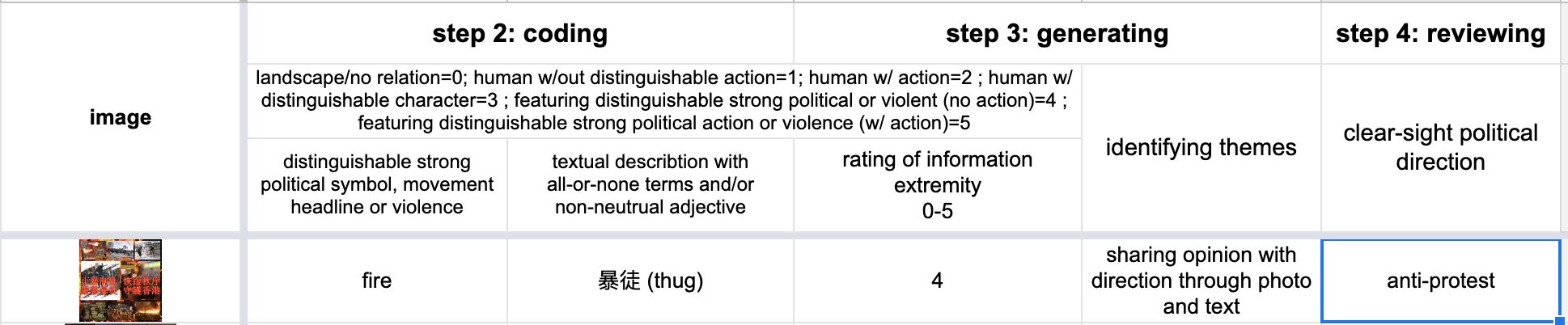

I followed the six steps of deductive thematic development by Braun and Clarke, I will now walk through one through four of practice in this case.

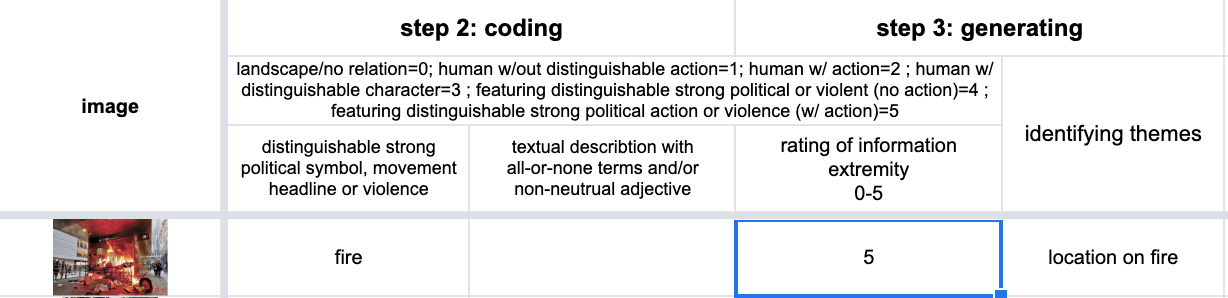

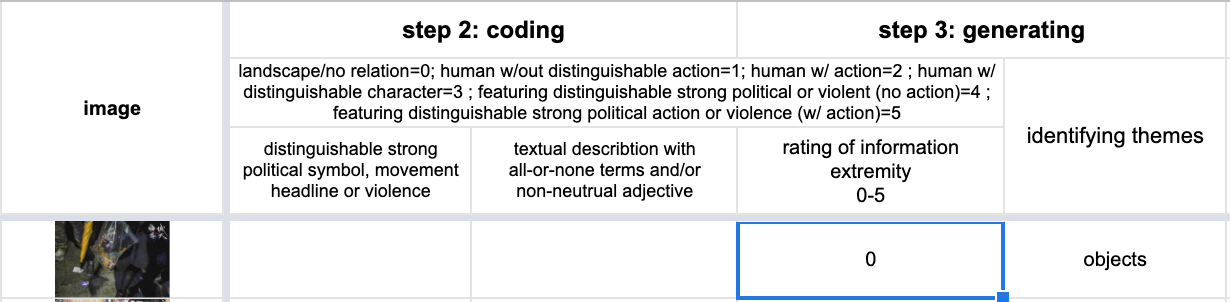

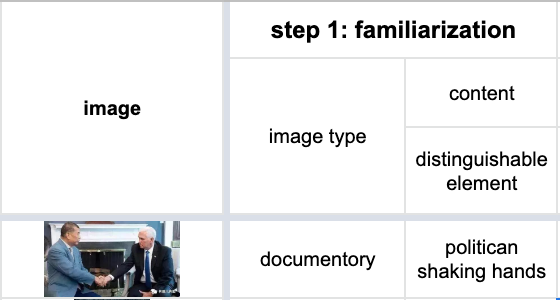

First, familiarization. I go through all the images briefly by labeling the image type and writing up the content of the images. For instance, I witnessed that there is a large amount of documentary photography and a lot of infographics and posters. For the content of each image, I focus on distinguishable elements like “police gathering,” “location on fire,” and “people getting arrested.”

0 No human, no significant relation to protest, no harm/danger, no all-or-none terms

1 Including human without distinguishable action

2 Including humans with action

3 Including human with action + political symbol, violence; + all-or-none terms

4 Featuring distinguishable political action or harm and danger

5 Featuring distinguishable political action, and/or/with the violence is happening

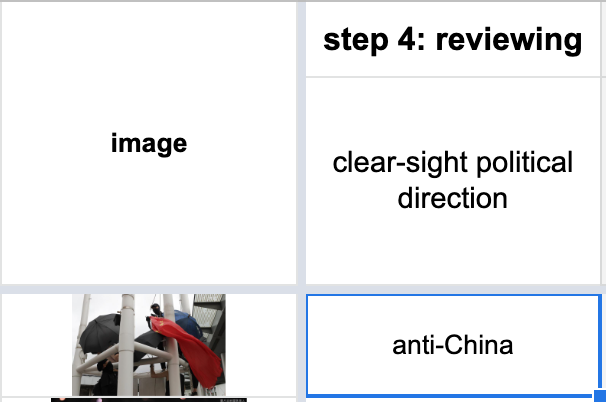

The fourth step is reviewing the themes. While I was reviewing each theme, I am observing if one image can represent a clear-sighted political opinion. For example, I argue that an image of the police and the people they are confronting can not represent if the image is telling the story of supporting the Hong Kong police or not supporting the Beijing government. Maybe the person who posted such a photo has a story to tell, but the image itself could not indicate such a political opinion direction.

Here is an example of an image carrying a political opinion direction. This is a documentary photography of protestors removing the Chinese national flag. This image itself holds a strong emotion and political opinion. However, the user who shared and re-shared this image may have an opinion than this story, but that would not be part of the analysis.

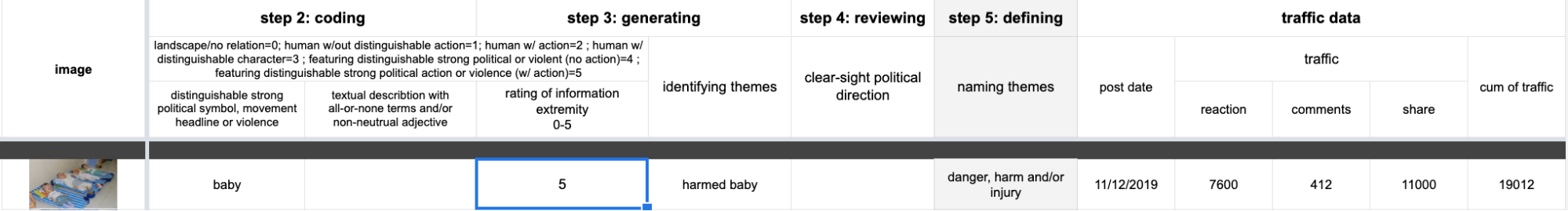

The second step of the coding and the third step of generating themes are overlapping in the process. In order to process the political nature of the images, I wish to discover if images can present opinion differences. I attempted to distinguish if an image has a strong political symbol, if it included a protest tagline, or if the image is featuring violence. Over 50% of the images are a combination of photos and text, so I looked for textual descriptions with all-or-none terms and/or non-neutral adjectives. This process is looking at the image itself, excluding the hashtag and/or any text posted along with the images. Only texts within the image are considered. I want to find out if the travel speed of an image is related to the extremity of the content, so I generated a rating rule for content extremity. While I was rating each image, I started to identify patterns of the visual language in the images.

Most of the images that carry a clear-sighted political opinion direction are infographics or posters. Even Though emotion and opinion travel faster through image than text, images that include text are still the fastest way to determine opinion.

Result of Analysis

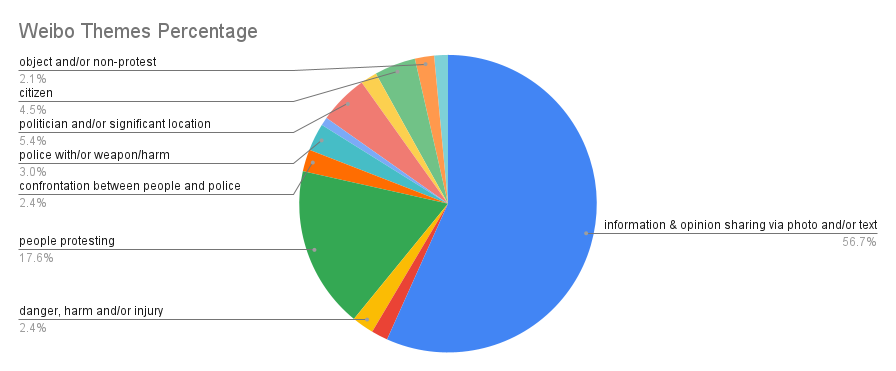

After familiarizing myself with the data, coding themes, and generating and reviewing themes, I defined the protest images with the following 12 themes. Information and opinion sharing through photo and/or text; information and opinion sharing through art; danger, harm, and/or injury; people protesting; confrontation between people and police; police with weapon or police and harm; police without action and harm; politician and/or significant location; public figure; citizen; object and/or non-protest related; censored information.

Discussion

This is a study of images, yet I found out that over half of the images, people posted are different formats of infographics. Infographics condensed textual information into an easy-to-share, reading-friendly communication format, with the support of graphic design and photography or illustration, carrying through many emotions and opinions.

Beyond texts, the themes of these images are reflecting the main topic of the protest: political opinion, police, and violence. The themes of violence are shadowing many criteria. Police brutality, rioting, harm, and injury. The confrontation between police and people, the confrontation between people and people. Fear and anger are penetrating each image. However, the speed of travel of images can not be determined by harm and violence. Among the top five traffic of images, the extremity rating of each result is under 5 in every search entry on Weibo. A similar scenario appeared on Facebook, where only one hashtag, “chiNazi” broke this pattern. An image of babies with birth defects has the highest traffic.

Conclusion

The themes of still visual media posts during the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests across Facebook and Weibo are the following: Information and opinion sharing through photo and/or text; information and opinion sharing through art; danger, harm, and/or injury; people protesting; confrontation between people and police; police with a weapon or police and harm; police without action and harm; politician and/or significant location; public figure; citizen; object and/or non-protest related; censored information.

The relationship between themes versus hashtags/search terms, platforms, and regions is not significant, similar themes are identified across both platforms that are very popular in Mainland China, HK, and the rest of the world.

However, such weak relations between search entries and platforms could indicate that the protest images can reflect the existence of public opinion polarization. Across both platforms, people are discussing protest and law, people are debating over police and violent acts. However, the same theme appears under #chiNazi and “废青(garbage youth),” two phrases carrying the opposite political opinion. Many users are using the same documentary photography to tell many different stories, people are re-sharing the same screenshot from government websites to express different opinions.

References

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, no. 2, 2006, pp. 77–101.Shanahan N,

Brennan C, House A. Self harm and social media: thematic analysis of images posted on three social media sites. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027006. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2018-027006

Widiatmojo, Radityo, and Moch Nasvian Fuad. “Thematic Analysis on COVID-19 Photojournalism in Indonesia.” Komunikator (Yogyakarta, Indonesia), vol. 13, no. 2, 2021, pp. 112–124.

Wetzstein, Irmgard. “The Visual Discourse of Protest Movements on Twitter: The Case of Hong Kong 2014.” Media and Communication (Lisboa), vol. 5, no. 4, 2017, pp. 26–36.

Pila, Eva, et al. “A Thematic Content Analysis of #Cheatmeal Images on Social Media: Characterizing an Emerging Dietary Trend.” The International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 50, no. 6, 2017, pp. 698–706.